Do you remember Facebook Albums? I hope you don’t. There are too many of them, hiding in the gnarled bunions of my digital footprint - recklessly assembled agglomerations of teenagers with frosted tips and side partings clad in Adidas tracksuits and Hollister hoodies, striking suspect poses on school tours, hunched outside shopping centres, lying drunk in wet fields.

Every generation is doomed to live with the sartorial sins of their time and endure the jeers of their offspring. Their reward is that they have full licence to act smug when the trends inevitably return: flared jeans, mullets, loud oversized tracksuit tops, you name it.

Fashion, public opinion, and political concerns move in cycles. The way we chronicle the greatness or mundanity of our day-to-day lives is not. Your mum might have had a crap haircut in 1978, but the proof lies in faded pictures in some shoebox, if it exists at all. Even more recent generations like 90s kids, those early Millennials that now own sensible three bedroom houses in Phibsborough - their Tamagotchi days of yore are safely nestled away either in their memories or hard-to-access media like video recorders, early digital cameras, or disposables.

If you were born when those 90s kids were in the salad days of their youth however, say 1993-1999, you came of age during a rather unfortunate time (if you’re easily embarrassed). A time when your bad decisions and your awkward phase would not be frozen in a photographic moment; but vomited in a giddy stream of consciousness directly into the permanence of the internet. The nascent social media age. Like a generation of child stars thrust into a spotlight they didn’t really know was there, we were not the first users of these platforms, but we were probably the most unsophisticated.

Welcome to Generation Guinea Pig.

The post-2008 internet was briefly a bit sexy and dangerous and it is still heavily romanticised. Blogging became a mature and exciting art form - it brought a ton of new minds and writers into the fold and opened up a raw, confessional niche on the internet that these days mostly lives on either in podcasts or, for the more cautious, in secrecy through anonymous subreddits. New media companies like Gawker and Vice were tackling the established giants and cornering a new audience. Then you had all the new, fun, poorly-policed crime: Limewire, LiveLeak, Silk Road.

All interesting stuff, deserving of its space in the Alexandrian Library of 2000s nostalgia. Nothing, however, was as formative as the new net that would knit us all together.

Everyone that came of age then will have a few of these funny staging posts in their life: when you got your first phone, when your house first got broadband, the first album you illegally downloaded, and what platform you used first. My generation’s adolescence coincided with the widespread adoption of social media, in that early, gunslinging Wild West era of Facebook, Bebo, MSN, and all the trimmings. We were the labrats - the guinea pigs - for a new kind of youth, one where you allowed your every thought to spill onto platforms that asked you, again and again: what’s on your mind?

And my god, ducks have never taken to water quite like legion of teenagers taking to the clunky UX of 2011 Facebook. Untethered from the naff text language and epistolary relationships of SMS messages, we suddenly had access to a platform where the only limitation was your own sense of shame - and here, even a Catholic education wasn’t enough. We would openly pose questions on what would become the News Feed: statuses asking what Maths homework we had, asking for an honest opinion on ourselves, or screening for prospective suitors (initially via Shift or Pass, and subsequently under the cloak of Ask.fm). The openness was outrageous, the naivety blindingly glorious. If you lost something at football training, you told everyone. If you liked someone, you told everyone. If you wanted to suddenly gain an air of newfound mystique, you updated your relationship status: It’s Complicated.

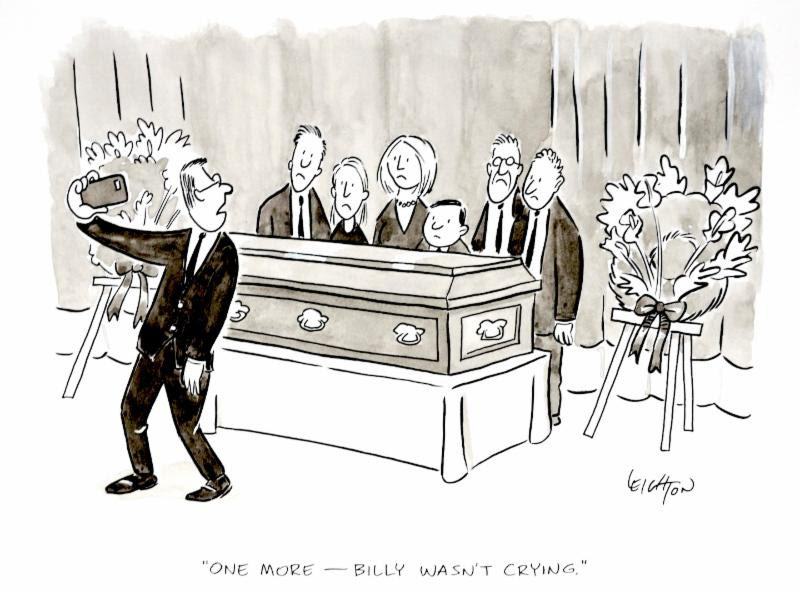

No one really knew what would happen when you put these tools in the hands of children. I guess we’re still finding out. Is it positive or negative? In the long term, would it turn us into school shooters, or make us value relationships more? How does it affect adult intimacy? Does it smoothen the rifts and heartache caused by emigration, or just veil the symptoms until it’s too late to notice how lonely we are? These were platforms that originally started out in Harvard dorms and Bay Area garages as dating apps or blogging sites. Now, they were informing how we formed friendships, found partners, and dealt with grief.

We were cannon fodder for platforms desperate for users to fuel their ad engines, and by god did we provide. There hadn’t been quite enough horror stories, enough parental angst, or enough scandal to make the platforms dangerous yet. Most of us were still restricted to our designated hour of internet time at home, but the seeds of being chronically online were sown. Our changing sense of selves tossed up so many questions that we were happy to add to the teeming, chattering noise online. This was before parental controls on social media existed, and rightly so - our parents hadn’t a clue how any of it worked. How many of them missed Justin Timberlake’s memo and called it ‘The Facebook’?

The combination of half-formed prefrontal cortexes and early social media brought the inevitable shedload of gaffes. You would be tagged in grainy Sony Ericsson photos in some incriminating pose or accidentally reveal your true identity via a poorly-constructed Ask.fm question (in hindsight, probably the most supercharged cyberbullying tool ever invented). Some, through youthful exuberance and horniness, blundered their way into the wrong person’s Snapchat Best Friends (a gloriously chaotic product feature). Relationships that are now marked with best man speeches and marital vows started (and nearly ended) with Bebo Luvs. And god knows how many borderline war crimes were witnessed at sleepovers via Omegle (RIP) or ChatRoulette.

But this messiness was to be expected. We were the first generation in Ireland to come of age with new social media platforms. We will be the only generation ever to come of age at the same time as social media itself.

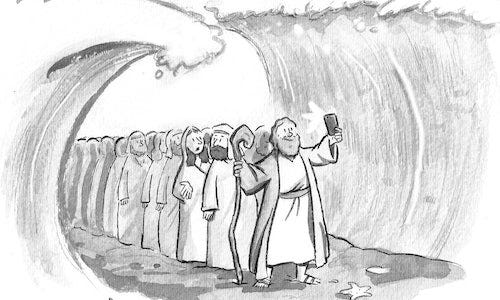

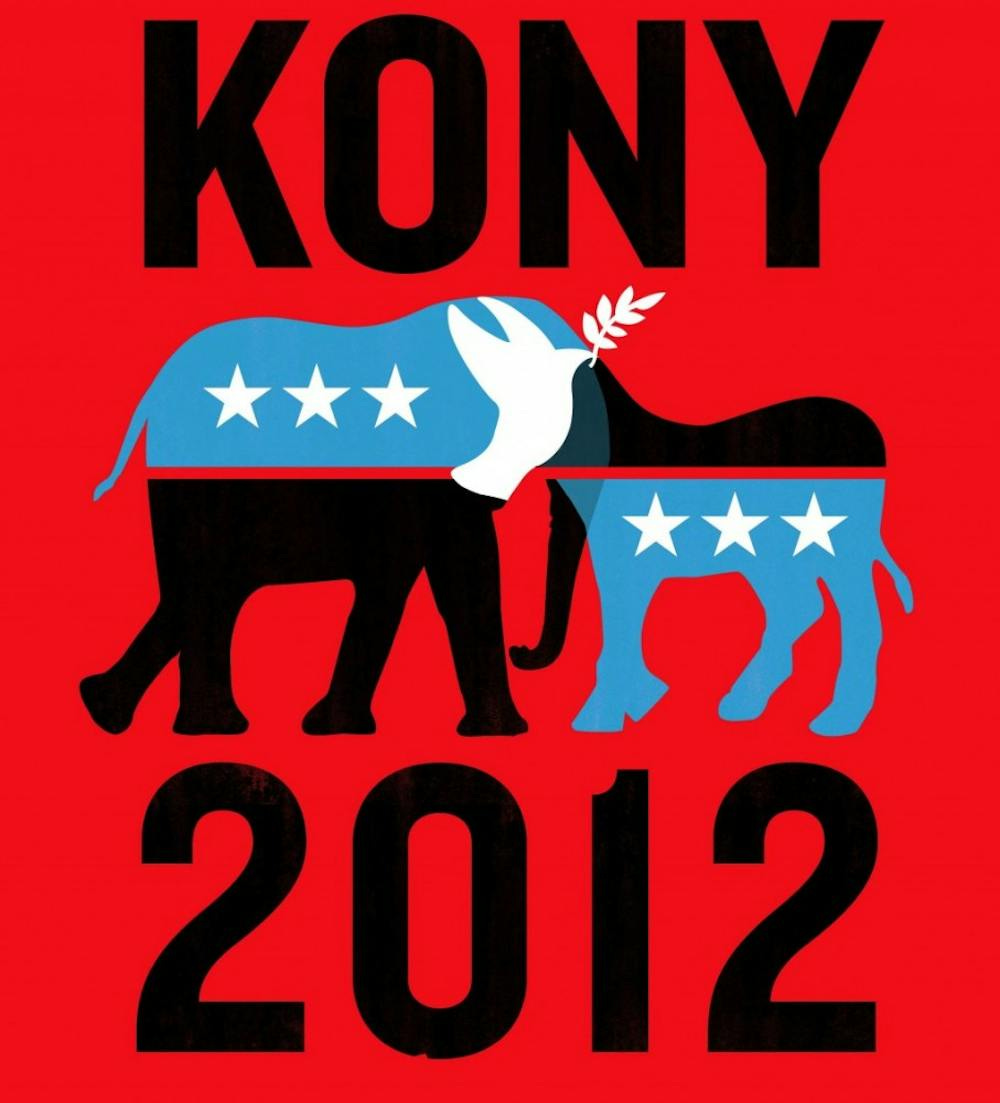

I’m not sure how long this heydey lasted. Like any generational moment, it was governed purely by sensation, not something as staid as dates. Still, it’s worth guessing. I would say it started roughly in 2010, when The Social Network hit cinemas and sent Facebook adoption into the stratosphere, where previously there was a fragmented blend of Bebo, AIM, et al. The Guinea Pig era rollercoastered through generational moments like the anticipated end of the world in 2012, Matt Cardle’s narrow X Factor win, and the pursuit of Ugandan militant Joseph Kony.

When did it end? When did our guards come up? That’s a tougher question - knowing when novelty wore off and something else (familiarity, and subsequently contempt?) set in. We were used to daubing our thoughts in permanent ink all over the walls of the feed via statuses, stolen jokes, and reshared posts. The introduction of Stories (on Snapchat in 2013, and Instagram in 2016) introduced an ephemeral feel to what previously was there forever. You could post something and it would be gone the next day. That was new. Is posting all this stuff online somehow dangerous or unwise? Should our opinions have a sell-by date? What the hell is screenshotting?

Then there was the retroactive social punishment of celebrities, athletes, and politicians for past tweets, Snapchat screenshots that emerged, or leaked groupchats revealing more than the senders had intended to share. The Guinea Pig Generation started applying for jobs in 2015 or so, and prospective employers had started googling them. That was the final nail in the coffin.

The interesting thing in watching the Guinea Pigs grow up is observing how we are now probably the most conscious of our screen time, digital footprint, and how much personality we’re willing to reveal online. A multitude of studies examining the harms of social media and watching celebrities self-immolate on Twitter has spurred this on. Many of my friends have deleted platforms: Instagram, Facebook, Twitter - a cleanse if temporary, a purge if permanent. Some have deleted and restarted their online profiles - more of a reincarnation.

With the passage of time, it would be easy to say that the internet, or social media specifically, has become less fun. It has become, some say, less social. Sure, doomscrolling is bad, but there is good evidence to show that being on your phone isn’t inherently harmful, and that social media can actually boost your mood and happiness when it’s used for connecting with friends and family. In the regular old media though, social media is pilloried: it’s used as an engine to rig elections, bully people, sell you shit you don’t need, and make your aunt a bit of a racist.

A glut of new features, redesigned newsfeeds, and algorithms marked and reshuffled like a Vegas blackjack deck are all but a thin veneer over the truth: the earliest days of social media, the adolescence - your adolescence - might just be as fun and innocent as it was ever going to be. Logging onto any platform now brings a torrent of negative, harmful, or merely (!) upsetting content, if you want to engage with it. We are lambasted with graphic videos from the latest war(s), infographics offering cutesy explainers on genital mutilation or systemic racism, and endless polemic on any number of tiresome topics from the political sphere.

But this is a reflection of Old Person Internet. If social media (platform agnostic) can reliably do one thing, it is confirm your biases. It doubles down on serving you either what you agree with or what you know that you hate, massaging it into the folds of your brain. That means the Guinea Pigs now get boring stuff like housing crisis discourse or Reels on how to sleep deeply where previously we had, I don’t know, Dude Perfect trickshot videos?

This is not an oral history of some weird little moment in internet history as much as it is a defence of the inalienable right of teenagers: to be idiots. They deserve it. The feeling of invincibility and sense of intoxicating, heady certainty is so worth the subsequent cringe. The tough part is protecting that innocence now that growing up online is the norm.

On TikTok (which is rapidly becoming gentrified and will soon be a bit lame, as nature insists) the kids are still having fun, in new, pleasantly stupid ways. To them, we are over the hill, on the scrapheap, finished. And as I sit here, scrolling through my targeted ads for pension schemes and osteopaths in my area where once there were hot young singles, I wish them only the joy that every dopamine-tinged notification brings. And that when they remember these times, just the rosy nostalgia of a woman finding the faded disposable snap of herself, with shoulder pads and a perm.

This Edition’s Recs

Coming of Age at the Dawn of the Social Internet

Online platforms allowed me to cultivate a freer version of myself. Then the digital world began to close off

by Kyle Chayka in The New Yorker

Read it because: Chayka is a writer I really admire. He writes with such care about how the internet affects and shapes us. This piece, a Millennial’s nostalgic exploration of his life growing up online, helped me to finally write down my own thoughts this week on guinea pigs and labrats and what the internet means when you’re young.

Carbon Offsets (Taylor’s Version)

The pop star’s use of hazily defined offsets to deflect criticism perfectly illustrates how the offsets market works in practice

by Kate Aronoff in The New Republic

Read it because: it’s worth thinking about how much more well-informed the world would be if every issue was somehow explained through the lens of Taylor Swift. She has a reputation as a climate villain (her private jet apparently spent 16 days airborne in the first six months of 2022), but is eager to make amends to this image. Swift has (allegedly) purchased carbon credits to offset the egregious costs of her travel, which leads us to a problem that sustainability experts have been grappling with for a while: carbon credits are largely worthless.

How a Script Doctor Found His Own Voice

For decades, Scott Frank earned up to three hundred thousand dollars a week rewriting other people’s screenplays—from “Saving Private Ryan” to “The Ring.” Finally, he decided to stop playing ventriloquist.

by Patrick Radden Keefe in The New Yorker

Read it because: Patrick Radden Keefe earned many admirers for fine books like Say Nothing and Empire of Pain and this profile sees him in his usual eagle-eyed form, seeing into the soul of Hollywood scriptwriter Scott Frank. Frank is the genius behind dozens of reworked masterpieces but this piece is about how after years of helping others, he has taken ownership of his gifts for himself. If you feel like you’re being pulled in ten different directions in work or your personal life, this is the piece for you.

That’s all for this week folks - let me know if you enjoyed the read (you can tap the ‘like’ button, reply to this mail or comment below) and if you know someone who would enjoy - just forward this mail.

Best so far forsure

Terrific musings